Does your photographic film or microfilm storage area have the faint smell of vinegar? Is it acrid enough to make your eyes water, or affect your breathing? Are you and your staff afraid to enter the room because they instinctively know something is not right? If the answer is yes to any of the above, your microfilms and negatives are probably suffering from vinegar syndrome! This resource explains how to detect acetate film base degradation, successfully manage a film collection, and prevent vinegar syndrome from destroying your collections.

About film substrates

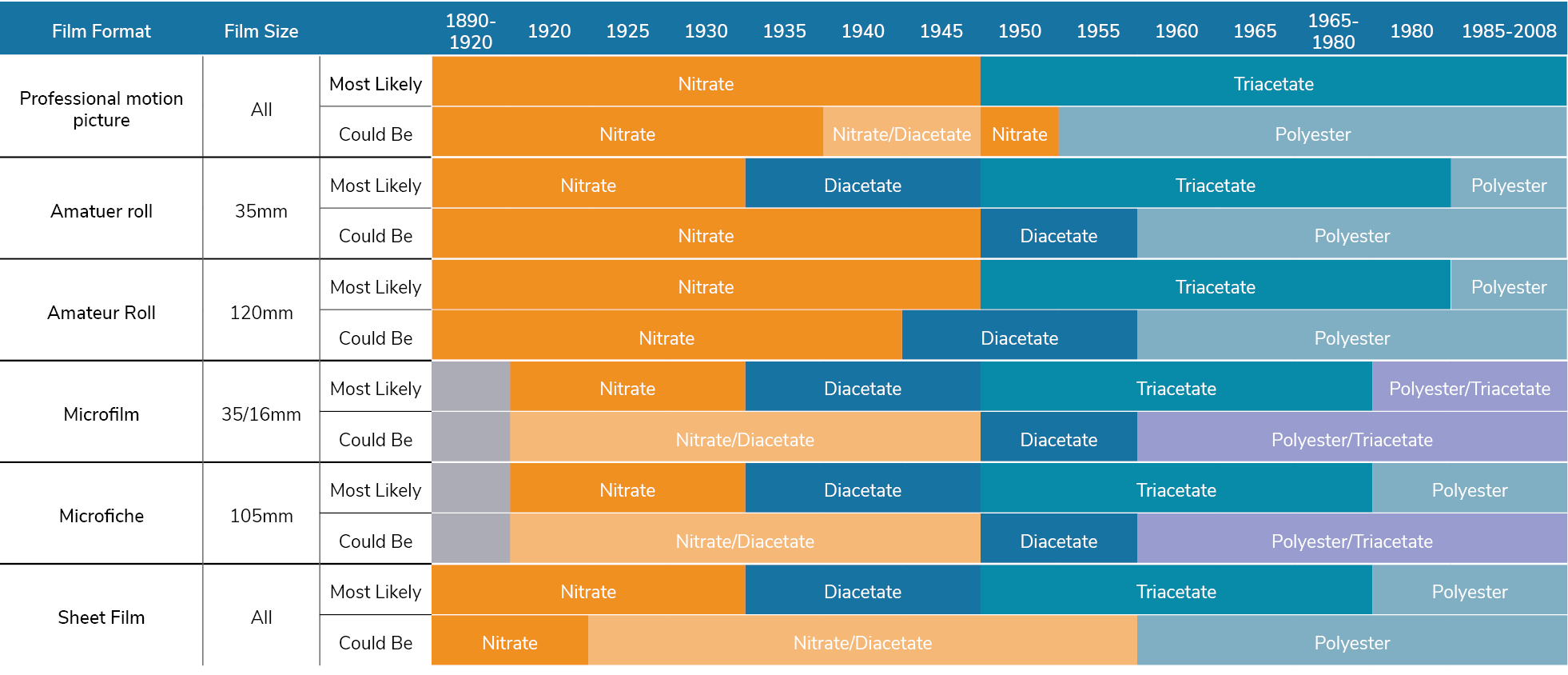

Photographic materials have been produced with a variety of chemicals and substrates since their advent. In the early years, from 1890 through to the 1930s, nitrate (or nitrocellulose) base was used for cinematographic, photographic, and microfilm substrates. This proved to be a rather dangerous decision; you’ve probably heard stories of them being prone to spontaneous combustion! In the 1930s, and certainly from the 1950s in New Zealand, most film substrates were manufactured using a cellulose acetate base, which (in homage to its predecessor) was known as “safety film”. Scientific tests spearheaded by Kodak suggested this film had a life expectancy of up to 100 years and although this is true, it is only accurate if the film is stored correctly. Acetate film was used in New Zealand as late as the mid-1990s by some organisations — in fact, NZMS was the first to shift to polyester in June 1990. Polyester has a particularly rugged plastic base, is extremely stable, and offers a life expectancy of 500+ years when properly processed and stored.

What is vinegar syndrome?

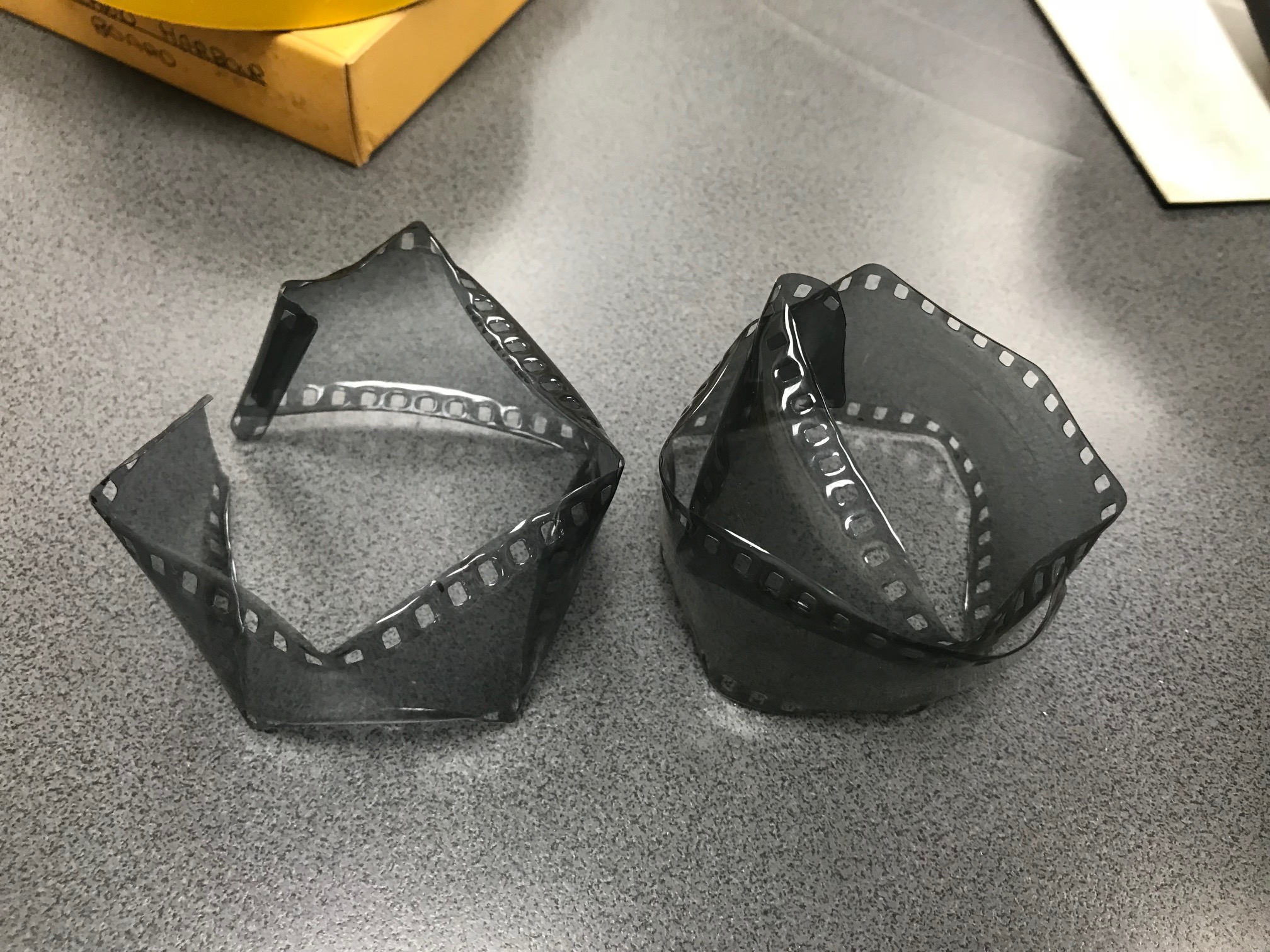

Acetate film has two significant weaknesses, but luckily both are manageable! Firstly, it is very prone to damage, even the slightest nick in the side of the film excessively increases the possibility of tearing. However, its more insidious weakness is its substrate which is prone to a slow form of chemical deterioration called vinegar syndrome. This causes the substrate to buckle, shrink, and become very brittle — any of which can degrade or completely destroy images and precious information in the emulsion layer.

What does it smell like?

You can normally smell vinegar syndrome before you can see it. The side effect of the film substrate breaking down is the production of acetic acid: the biggest sign of a deteriorating acetate collection is the smell of vinegar!

“Chemical reactions influenced by heat, moisture, and/or the presence of acidic vapours from nearby degrading film cause acid to be generated within the cellulose acetate support. From there it diffuses into the gelatin emulsion and often into the air, creating a sharp, acidic odour.”

– A-D Strips User Guide.

What does it look like?

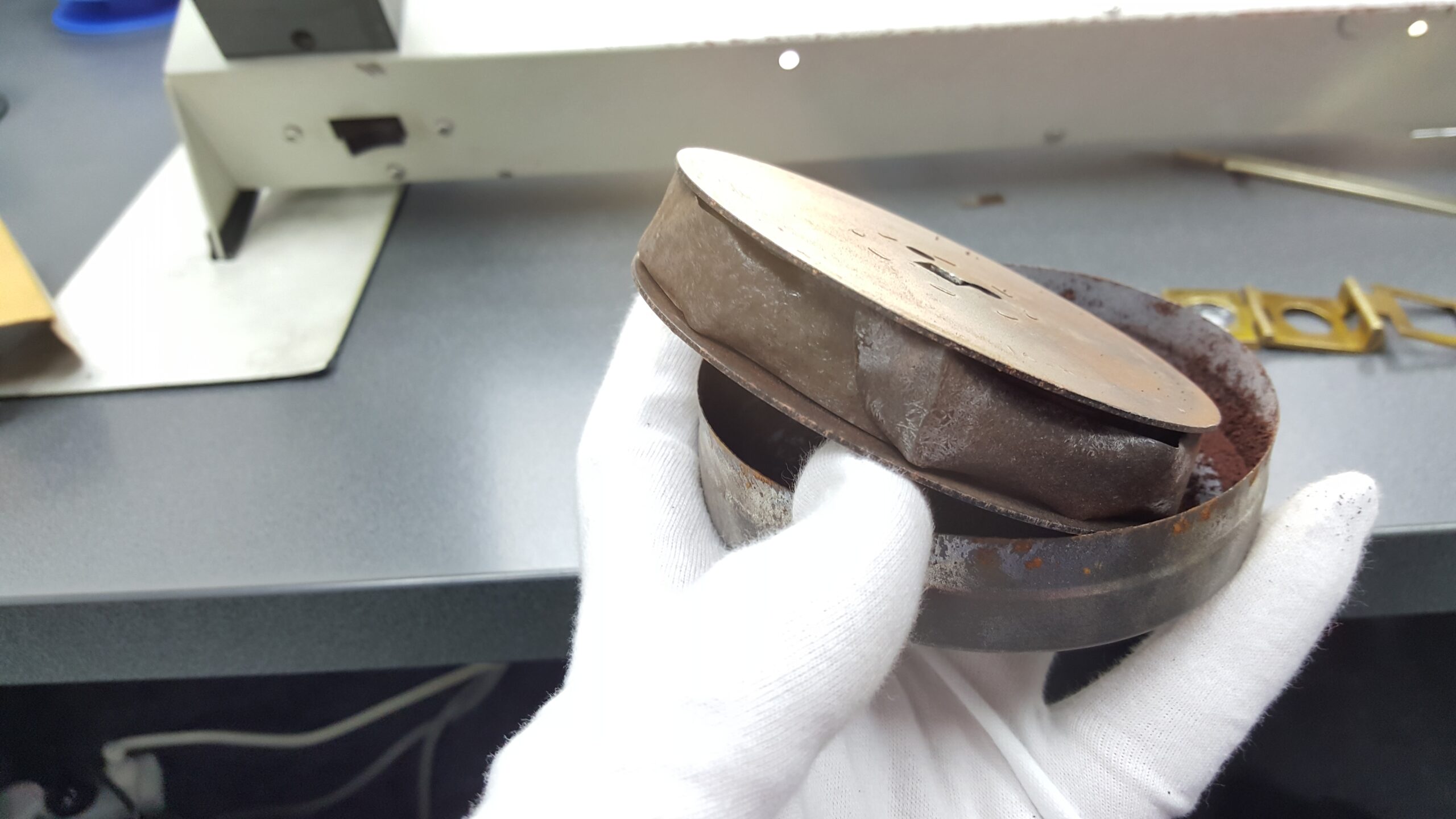

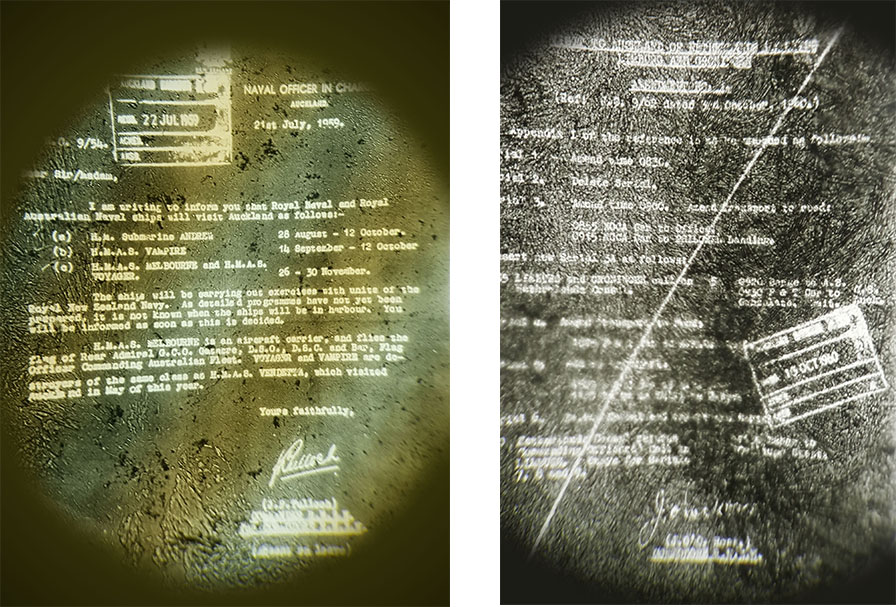

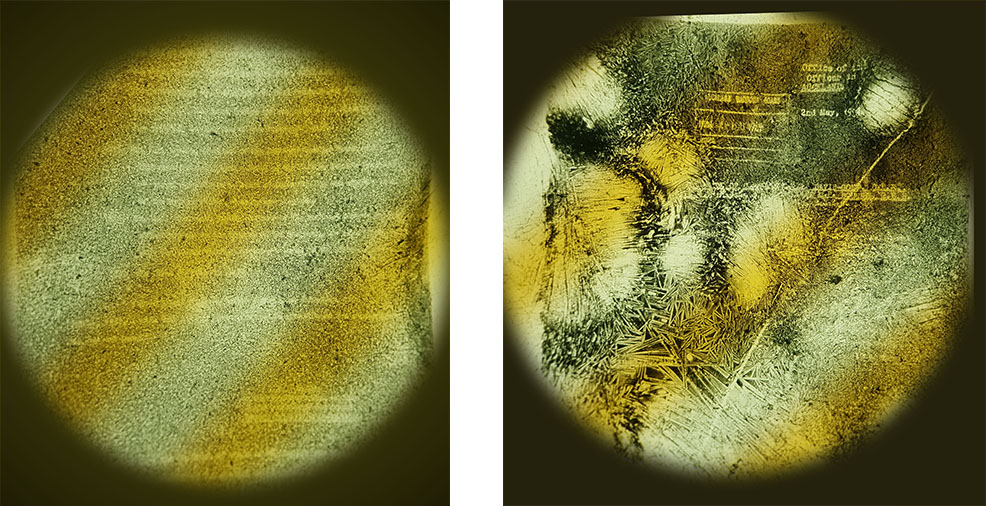

Here the microfilm is extremely buckled and the emulsion has dried out and is shedding off in parts. The layers of the film on the roll have actually fused together and the emulsion has crystallised on the inner layers of the film. Less than 10% of the intellectual content (in the images) from this film was recoverable.

In the image on the right, you can see the emulsion has crystallised creating a blurred effect over the text — it often looks a bit like crazed ice over a puddle or lake.

The two reels above were produced in the same year and probably stored together for decades, so it was likely that they would be in a similar condition. However, without a proper assessment, there was no easy way to determine how severe the loss of information could be. After assessing the reels we discovered that they were both actually in slightly different conditions. This was probably due to the differing moisture content of each (how they came off the processor), or that one was stored close to a heat source such as a computer, radiator, or the sun through a window.

The example above shows a photograph that exhibits buckling and lines which are the early signs of cracks in the emulsion. These will steadily get worse and ultimately render the image illegible. Urgent action in the form of duplication or digitisation had to be undertaken promptly to save this photograph.

Storage Environment

To ensure the longevity of your photographic or microfilm collection, films are best stored in a stable environment that is as cold and dry as possible. Ideally, the temperature should not exceed 21°C and relative humidity should be less than 50%. They are best housed individually in acid-free paper, card sleeves, or boxes and stored in open or breathable containers. It is crucial to immediately isolate any items presenting symptoms of vinegar syndrome from the rest of the collection as soon as they are identified. If left with the collection the fumes from the degradation process will hasten the deterioration of other acetate films in their vicinity. Chilling will help to slow the degradation while they await further assessment and digitisation — although, you must think carefully about the introduction of moisture which can accelerate the degradation. At this stage, you should develop a conservation and management plan for your collection which will include ongoing assessment and a decision for duplication. This might involve transferring the image onto the more stable modern polyester film base, digitising the image, or a combination of both.

Assessment It is important to detect the degradation of your acetate collections early so that you can undertake remedial action. The first step is to assess the acetate film in your collection — make sure you don’t simply rely on smelling the vinegar odour as by then it may be too late to recover your data! Film can be made from acetate, nitrate, or polyester substrates. There is very little, if any, nitrate microfilm in New Zealand collections because nitrate was most commonly used in the movie industry. Acetate and polyester film look identical, which makes them challenging to identify. The production date of the film or microfilm renders good clues as to its substrate but there are some physical tests that can be conducted as well. One is an invasive technique called tearing, but the preferred option is light channelling, which is much less destructive and can easily identify acetate from polyester. NZMS staff are trained in a range of safe techniques to identify which substrate is present in your collections.

As mentioned, your nose also provides a terrific detection system, although at this stage your collection is in trouble! Films in the early stages of vinegar syndrome are easy to detect due to the recognisable smell produced. This is often known as the trigger point or auto-catalytic point where the degradation/decomposition accelerates exponentially. Assessment is critical at this time and adjustments may have to be made to both the storage environment and access. Temperature and relative humidity should meet current recommendations and acidity monitored with A-D Strips.

More visible signs are that the film can buckle and twist; the film structure starts to warp. In these situations, it becomes difficult to reformat as the film edge is no longer straight and can be unwieldy to duplicate or digitise. The film also becomes brittle and the emulsion can start separating from the base and crumbling away. Unless it is caught early on, the accumulation of acetic acid will destroy the images on your films. Crystallisation can be seen on the film and it will start to fuse itself together which makes it difficult, if not impossible, to handle.

During the assessment, an understanding of the scope of your collection can be built. For example, the number of images on a roll of film can be measured or the number of negatives in a box or sleeve can be counted. Any forms of taxonomy or indexing used for collection identification that you may have recorded digitally or in catalogue form also provide useful guidance. All this information can contribute towards understanding the extent of your ongoing storage (enclosures for the material as well as the environmental conditions), preservation, duplication, and digitisation costs. These are important factors for developing your collection management plan and ongoing funding costs.

Detection

Films in the earlier stages of deterioration can be detected via a more scientific method than your olfactory system by using the A-D Strip testing (Acid Detection) system. The litmus PH paper strips evaluate whether the films are undergoing acetate degradation. A-D strips come with a pencil that has a key indicating the different state of films. This can help to identify which films should be isolated, duplicated, or digitised. The A-D strip scale runs between 0-3, with 0 as stable (Blue) and 3 as undergoing severe degradation (Yellow). In the picture above, you can see different colour test strips reflecting the condition of the films they are sitting on (the strips were placed in the boxes with the films). You can purchase A-D testing strips from this website to monitor your acetate film collection and its potential degradation. If your film shows any signs of degradation or vinegar syndrome, it is crucial to act fast. We recommend you bring the collection straight into NZMS for a full assessment. Once appraised we can make recommendations and devise a plan to preserve of your data and records through duplication onto modern polyester microfilm or digitisation.

Conclusion

If you have microfilm or photographic negatives in your collection you may or may not have a plan for managing your collection. A plan is important and should factor in storage and access conditions as well as the containers the items are held in. You should have a good understanding of what is contained in the collection but often collections are inherited and only described at the macro level for example “City Photographer’s Studio Photos circa 1958”. At some stage, you will want to know what content you want to keep and digitise, and what you may discard. Most importantly from a longevity perspective, you need to know whether they are polyester, acetate, or nitrate — NZMS can help you with this. It’s timely to cite this quote:

“People say microfilm is old fashioned and therefore we should replace it. Paper is over 2000 years old and we still all use it. Just because something is old does not mean that it is no good. It just means it works. Microfilm is analogue, it is physical and it is secure. However, with the latest microfilm scanners you can turn microfilm into a digital format whenever you want to – the best of both technologies.”

Paul Negus from GenusIT (UK)

If you can smell vinegar around your microfilms or negative collection, you have a problem that needs addressing urgently. The extent of that problem can only be determined by having your films assessed. While proper storage can slow the degradation, the film will eventually need to be duplicated onto a modern preservation material or digitised. Here at NZMS, we are seeing more and more collections that have degraded to the point that the cost and ability to recapture have increased markedly or at worst the information is irretrievable. One thing you simply can’t do if you have the responsibility to ensure your collections are available for future generations is to shut the cupboard, or close the drawer, and hope for the best!

References:

- https://www.imagepermanenceinstitute.org/imaging/ad-strips

- Reilly, J.R. (1993). Image Permanence Institute storage guide for acetate film. Retrieved from: https://www.imagepermanenceinstitute.org/research/film.html

- https://www.nedcc.org/free-resources/preservation-leaflets/6.-reformatting/6.1-microfilm-and-microfiche

Further Reading:

- Case Study: http://www.micrographics.co.nz/digitising-glass-plates-for-the-sir-george-grey-special-collections-with-auckland-libraries/

- An opinion piece about the value of content contained on microfilm & its context: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/07/microfilm-lasts-half-a-millennium/565643/