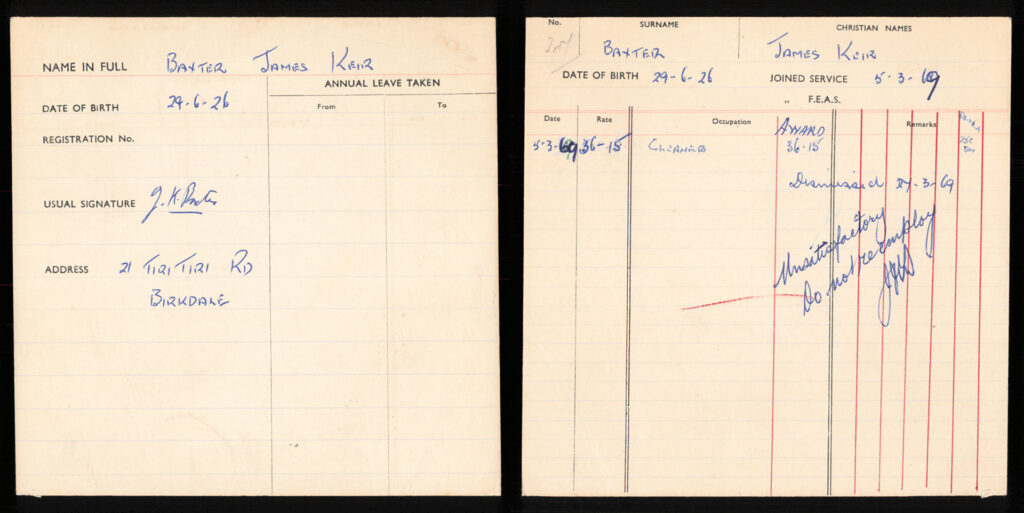

Image above: Colonial Sugar Company works at Chelsea, Birkenhead, Auckland. Price, William Archer, 1866-1948: Collection of postcard negatives. Ref: 1/2-000291-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22323187

The coral pink building of the Chelsea Sugar Refinery is an iconic structure in Birkenhead on Auckland’s North Shore. Recognised by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga as a category 1 historic place, it commenced operation in 1884 and remains New Zealand’s main source of sugar products. It is a significant part of the Nation’s history; not only is it the only sugar works to have ever been established in New Zealand, but is it also the longest continuously functioning works, making it one of our most important industrial landmarks.

Before August’s Alert Level 4 lockdown, our Auckland team had begun digitising Auckland Libraries’ Chelsea Archives. The collection includes over 5000 employee record cards belonging to the Chelsea Sugar Refinery, each describing individual employees through their personal details and employment history.

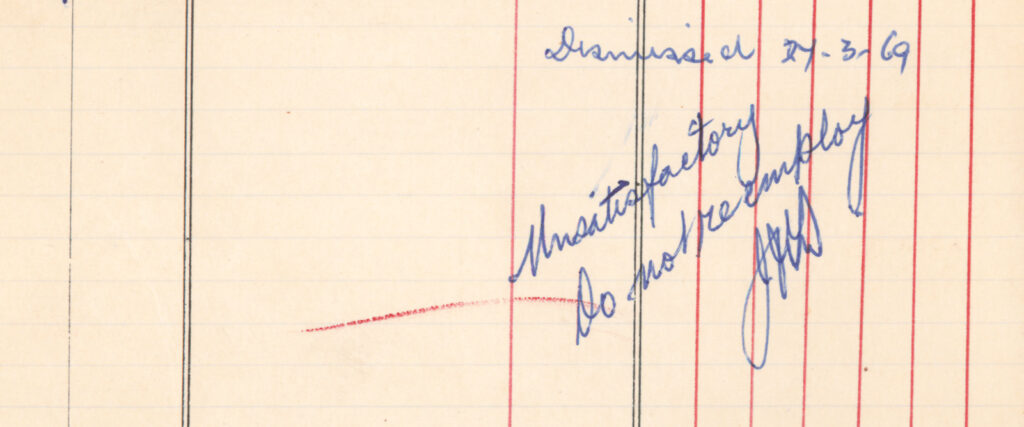

Surprisingly, our team came across an employment card for James K. Baxter, who is one of New Zealand’s most renowned (and controversial) poets and playwrights. He is often regarded as the leading writer of his generation and produced thousands of poems, plays, and articles during his short life (1926 –1972).

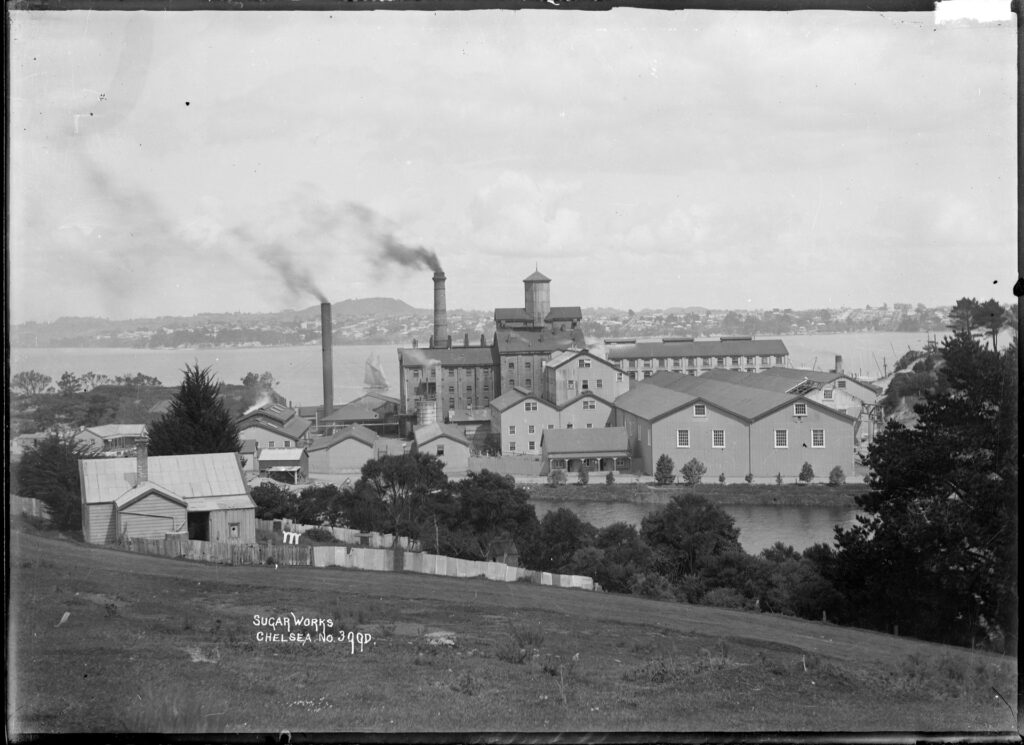

The card, dated 1969, states that he was fired and should never be employed at the factory again. This was the same year Baxter moved from Auckland to the remote rural settlement of Jerusalem (Hiruhārama) on the Whanganui River and established a community under the mana of the local hapū Ngāti Hau. In addition to his many literary accomplishments, some of which have received international acclaim, he has also been lauded as a bicultural trailblazer for his engagement with Māori and integration of Māoritanga in the foundation of his commune.

Baxter has always been a contentious figure in New Zealand’s history — and his legacy continues to be both problematic and complex. In 2019, a collection of Baxter’s personal letters were published by Victoria University Press revealing indefensible treatment of his wife Jacquie Sturm. This discovery triggered a re-examination of many aspects of Baxter’s life: from his attitude and behaviour towards women, as well as acknowledgement of Sturm’s influence on his willingness to embrace te ao Māori.

Long overshadowed by her famous first husband, Sturm has emerged as a unique and important voice in New Zealand literature. Notably, she was one of the first Māori women to gain a university degree, receiving a Bachelor of Arts from The University of Canterbury and a Master of Arts from Victoria University of Wellington.

Baxter’s short period working as a cleaner at Chelsea Sugar Refinery is well-known: he even wrote satirical poem expressing his dissatisfaction and loathing for the factory.

Baxter’s poem, Ballad of the Stonegut Sugar Works, is scathing:

I had the job of hosing down

The hoick and sludge and grit

For the sweet grains of sugar dust

That had been lost in it

For the Company to boil again

And put it on your plate;

For all the sugar in the land

Goes through that dismal dump

And all the drains run through the works

Into a filthy sump,

And then they boil it up again

For the money in each lump.

…

And though along those slippery floors

A man might break a leg

And the foul stink of diesel fumes

Flows through the packing shed

And men in clouds of char dust move

Like the animated dead.

The poem was published in an independent socialist magazine called the New Zealand Monthly Review in 1970. It is worth noting that Baxter’s impression of the factory was not shared by everyone. While it was regarded as a place of hard work, morale among the workers was high. The company offered its employees many benefits, including housing loans and job security. More information about Baxter’s time at Chelsea Sugar Refinery can be found in Auckland Libraries’ blog.

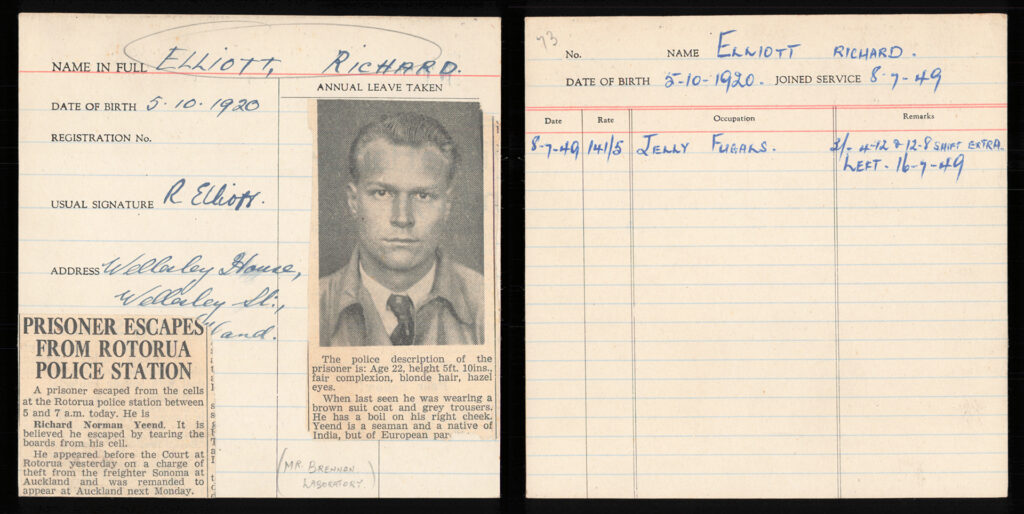

Another employee card that stood out to our technicians was one belonging to a man called Richard Elliott. His employee card has a newspaper clipping attached to it that details Richard Norman Yeend’s escape from a police station in Rotorua. This connection suggests that perhaps the name Richard Elliott was a alias…Yeend was in custody for the charge of theft, having been caught stealing from a freight ship in Auckland. Unfortunately, there is no further information and the man’s fate is a mystery.

Digitisation of Auckland Libraries’ Chelsea Archives means that the employee cards can be transcribed and an index of names can be created. Manually browsing the cards to find a name is very time-consuming and significantly impedes public use.

Being able to easily access primary research material like employee cards, or even Baxter’s personal letters, highlights the power held within archives to reframe and piece together history — it ensures that people can continue to look critically at what has been deemed “truth” and ask new questions.