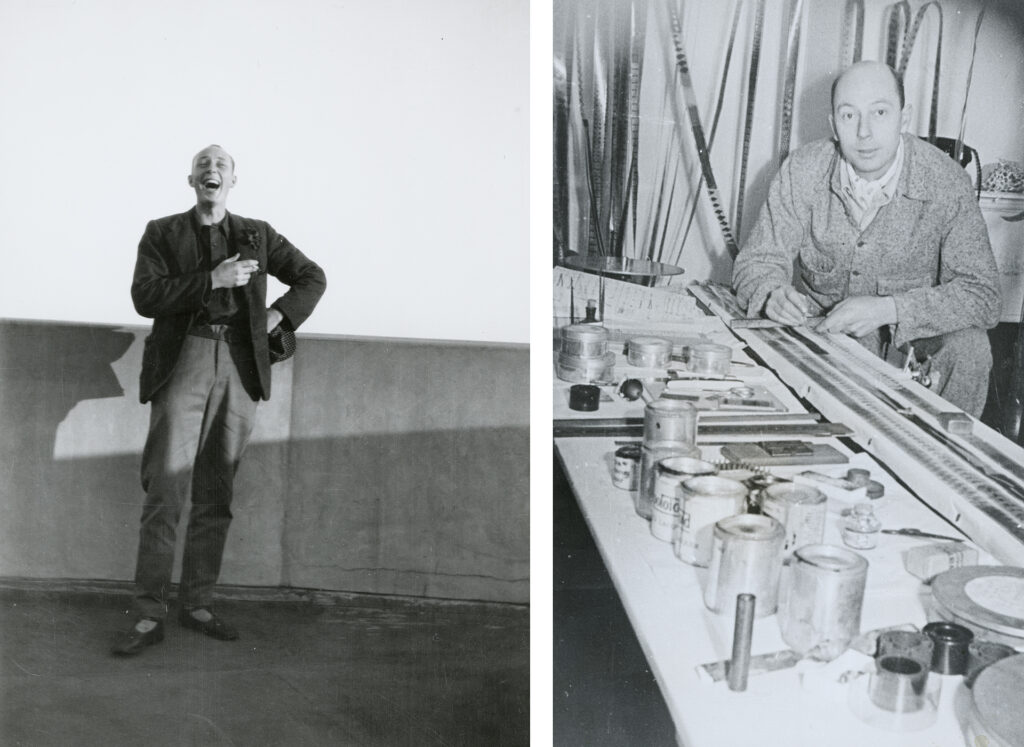

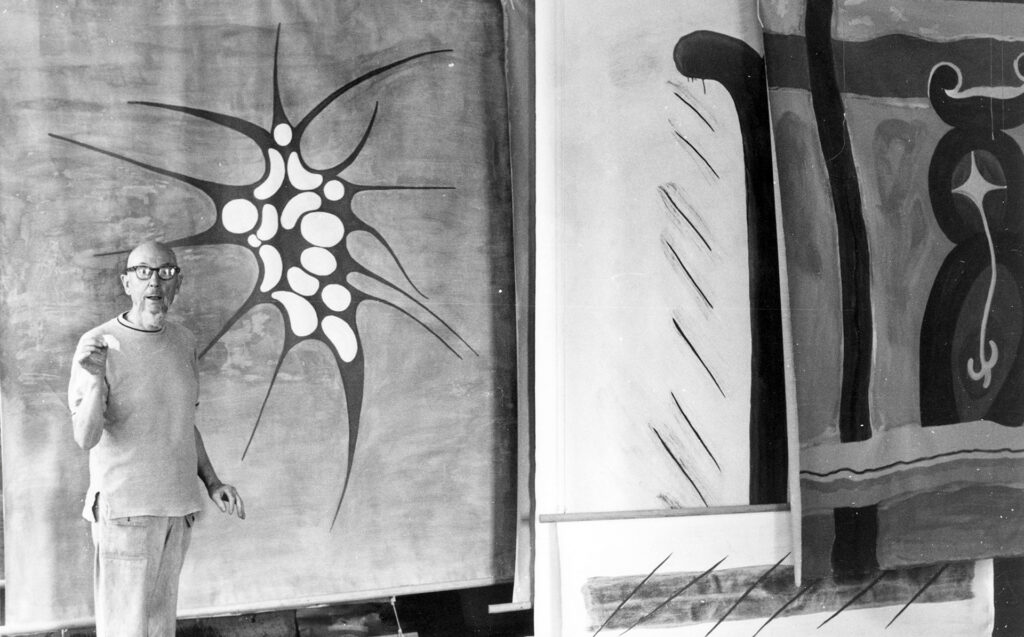

Image above: Len Lye with the kinetic sculpture Grass, 1961. From the Len Lye Foundation Collection, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre.

The Govett-Brewster Art Gallery is home to the Len Lye Centre which holds a diverse collection of material relating to one of New Zealand’s most renowned artists. Len Lye’s accomplishments are broad: he was known as a filmmaker, kinetic sculptor, painter, doodler, and poet.

A range of material from the Len Lye Foundation was recently digitised by the NZMS team in Te Whanganui-a-Tara/Wellington. The digitised material represents a sizeable portion of the Foundation’s holdings of Len Lye’s works on paper and photographs. Our team were honoured to handle and view this important material that exemplifies Lye’s lifelong fascination with movement — which was visible not only through his sculptures but within his drawings as well.

Who Was Len Lye?

Proclaimed by the Govett-Brewster and many others as “a one-man art movement spanning several countries and multiple media,” Len Lye’s progression as an artist is a complex and fascinating story. While a brief description can be read below, a more in-depth biography can be read in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography and on Govett-Brewster’s website.

Len Lye was born in Christchurch in 1901, but he spent much of his childhood in Wellington. Growing up, Lye was known to frequently visit public libraries, educating himself on art history and theory. His interests in film projection and kinetic sculpture were sparked during the year he spent living in a lighthouse on Cape Campbell where his stepfather was the assistant lighthouse keeper. Here, Lye would have observed the mechanics of the lighthouse first-hand and witnessed the flashing lights from its lantern’s beaming across the undulating waves.

Lye eventually returned to Christchurch to study at the Canterbury College of Art (now Ilam School of Fine Arts) under the artist Archibald Nicoll before travelling to Australia to learn basic animation techniques. Over the next couple of years, he also visited various Pacific Islands and for a time he lived among the villagers in Western Samoa, hoping to advance his study of art.

Later, in 1926, Lye moved to England where he became well acquainted with the avant-garde art scene and befriended several leading artists of the time. Eventually, he was accepted into the Seven and Five Society (of which Frances Hodgkins was also a member) and exhibited regularly with the group until 1934.

Lye moved to New York in 1944 and immersed himself in many different art movements including abstract expressionism and kinetic art. Over his career, Lye took a unique journey through modernism — first as a New Zealand artist working in London during the pre-war years, and later as a key figure in the post-war New York avant-garde art scene.

In his late seventies, Lye reconnected with Aotearoa when the Govett-Brewster offered to hold a solo exhibition featuring his kinetic sculptures. He was impressed with the ability of the people he worked with and their passion to realise his motorised sculptures on an even larger scale. This experience in New Plymouth prompted him to set up The Len Lye Foundation so that he could gift his entire archive of paintings, sketches, drawings, models, and manuscripts to the Govett-Brewster — ensuring the works remained cared for and managed after his death.

Since the 1980s, the Foundation and Govett-Brewster have collaborated to continue to develop Lye’s legacy. Not only do they manage and exhibit his past work, but they also regularly build new sculptures from Lye’s plans that would have been unbuildable in his day. The Len Lye Centre was built in 2015 to function as a dedicated venue for Lye’s work and it is the first New Zealand art museum dedicated to a single artist.

What Was Digitised?

The collection has been in the care of the Govett-Brewster since 1980 and has advanced rapidly over the last 20 years in terms of cataloguing, rehousing, and digitisation. The material that was digitised by NZMS contains a variety of subjects and mediums, including works on paper, photographic prints, and negatives.

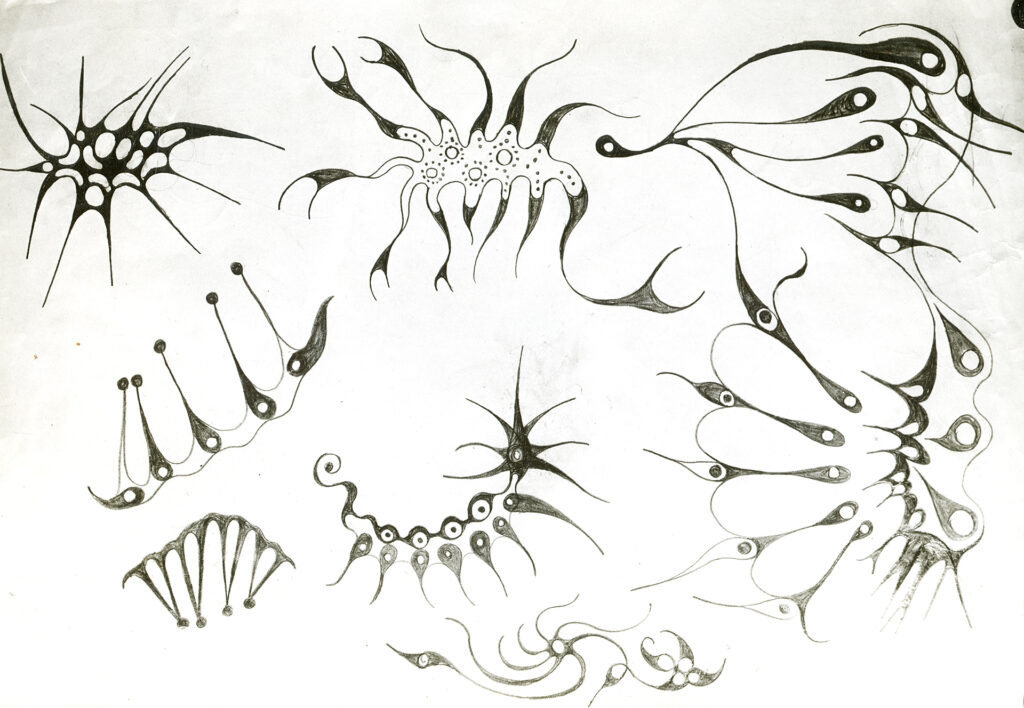

Most of the works on paper can be classified as Lye’s “doodles” which are small automatic drawings composed on scraps of paper. These drawings are an important part of Lye’s creative process, there are hundreds of them in the collection and they are usually untitled and undated. Our team were tasked to digitise 631 of these works on paper and to ensure the best possible result we used our high-end flatbed SMA scanner. This meant we could capture TIFF files at a resolution of 400ppi (pixels per inch) and achieve a 24-bit colour profile.

The photographs were from Len Lye’s personal archive and document his artwork, in particular his sculptures, as well as his family, friends, and domestic life. These photographs fall into two distinct categories: prints (physical positive images on paper) and negatives. Our team digitised 1267 of these photographs in total and used our Lanovia scanner. It provides an exceptional level of resolution having been built specifically to deal with detailed photographic images. We captured the prints to 500ppi, 24-bit colour and the negatives were captured to 5000PLE (pixels per long edge), 24-bit colour. PLE is often a more useful measurement when digitising particularly small or detailed items like negatives.

The resulting TIFF files we created are considered digital preservation masters and each image is very large — ranging from 10 to 60 MB, depending on the amount of detail that was captured. Since these images cannot be opened quickly, we also created smaller JPEG files from the original TIFFS for fast access and viewing. The Govett-Brewster aims to eventually allow public access to the digitised items, but the primary purpose for the collection’s digitisation was to support curatorial research. Paul Brobbel, the Len Lye Curator at Govett-Brewster, explains that with digitisation “the full scope of the collection comes into view more easily, and our knowledge of Lye and his practice can deepen.”

Lye’s Doodles

While the breadth of the collection is crucial to our understanding of Lye as an artist, it is especially true of the pieces described as “doodles.” This method was at the heart of Lye’s practice throughout his career and underpinned his stylistic choices by resonating with intuitive movement.

In his typical abstract fashion, Lye said that doodling “cultivates a vacuous seaweed-pod state of kelp as a skull which is attached to a pencil betwixt the arm and the fingers held doodling in turn ‘twixt you and the paper in a rather bemused, empty, harmonious state of an attitude, eyes periphering said paper.” This approach to drawing is related to surrealist automatism and aspects of abstract expressionism and informed his entire art practice through painting, photography, film, and sculpture.

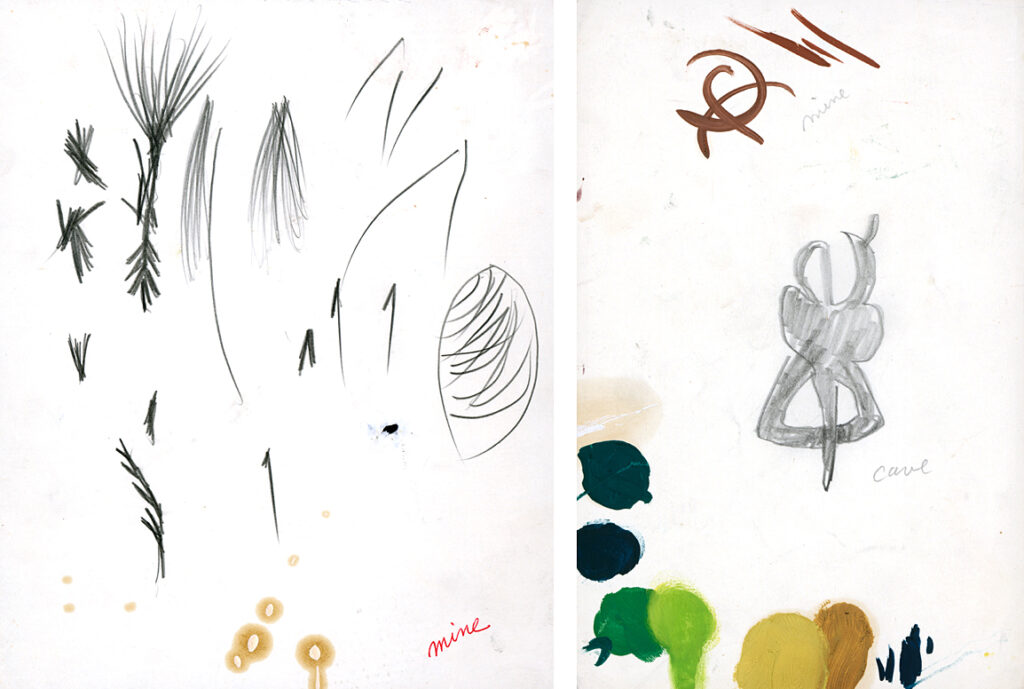

Lye was known to draw on any material that he had in hand – e.g., the backs of envelopes, newspapers, packaging, or graph paper. He was a prolific artist, and the Len Lye Foundation holds over 1400 of his works on paper. These works range in subject and style: his early portraits and figure studies are descriptive and realistic, likely influenced by conventional art teaching, while his later works depart from this completely by morphing into “doodling” and are much more in tune with his fascination for energy and motion.

Alternatively, Lye described some of the doodles he created as cave/mine drawings. Paul Brobbel explains that “these were experiments in identifying the workings of the ‘old brain and new brain’ creativity at play in his work. Lye felt his work was adept at drawing inspiration from the ancient intellect of mankind’s collective old brain. These ‘doodles’ were exercises in automatic drawing in which he would identify and categorise each as either coming from the ‘cave’ (our shared ancient brain) or otherwise as coming from ‘mine’ (his own modern ‘new brain’). This exercise helped Lye refine his artistic process and it also provides us with an insight into his workings and sense of experimental drawing.”

Lye’s doodles sometimes have notes and inscriptions on the back that can help curators identify related works elsewhere in the collection. For example, an untitled painting may have an accompanying sketch or ‘doodle’ in the collection that carries a title or a date. This type of research into the drawings in the collection is crucial to Govett-Brewster’s care of the collection as a whole.

“Lye’s drawings are the single largest body of artwork in the collection and represent his practice from the 1910s through to the 1970s. The large batch NZMS has undertaken to digitise is the most challenging to work with in terms of size and complexity. This now means Lye’s drawings are close to 100% digitised, which is an exciting proposition for researching with this collection.”

– Paul Brobbel, Len Lye Curator, Govett-Brewster.

Experimental Films

Len Lye is also incredibly well-known for his animated experimental films, particularly in the USA. He began his journey with filmmaking in 1929 and at the time he was unable to afford a camera, so he experimented with painting directly onto the film instead. This can be seen in his film called A Colour Box (1935) which pioneered the use of direct filmmaking and won a medal of honour at the International Cinema Festival in Brussels. It is often considered one of the most significant works in the history of animation.

Lye’s innovative technique of painting or scratching patterns directly onto film gives his work a witty and whimsical quality. He used processes of colour printing, jump-cutting, stop-frame animation, and synchronising visuals with music to create a truly innovative films. A lot of his work shows influences of Māori, Samoan, and Aboriginal art. This is particularly noticeable in the film Tusalava (1929) which tells the story of the witchetty grub, a source of food for the Aboriginal people. Lye had an enduring interest in Pacific imagery, patterns, myths, and legends and this is not only found in his films but also in his paintings, drawings, and artistic theories.

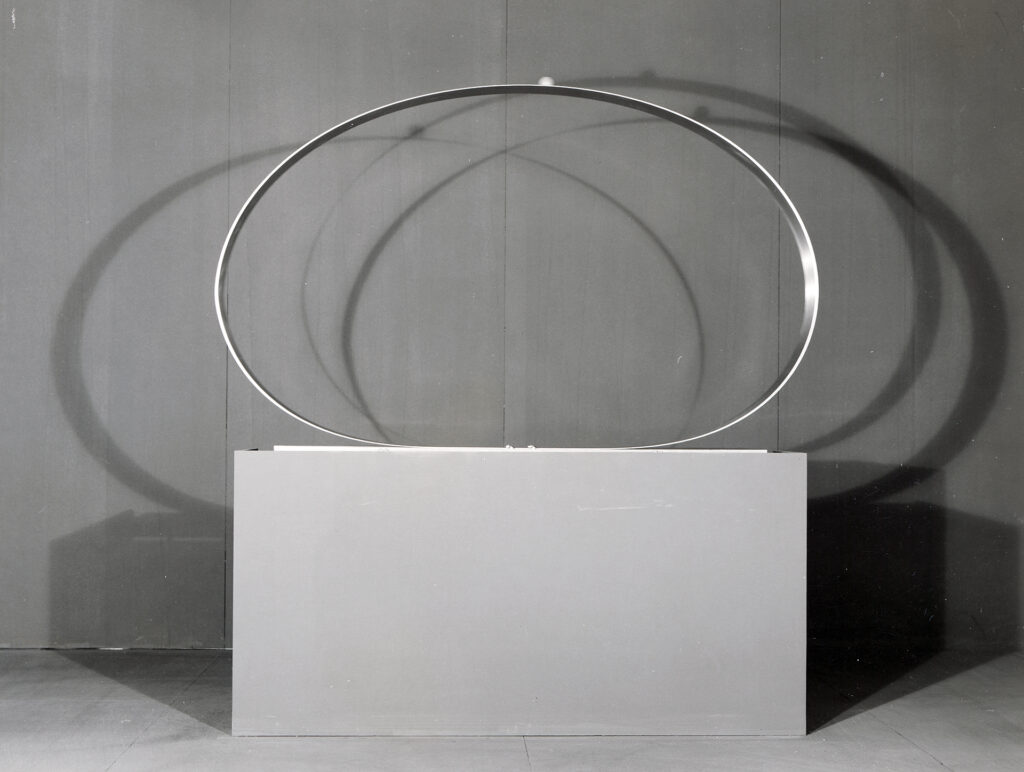

Kinetic Sculpture

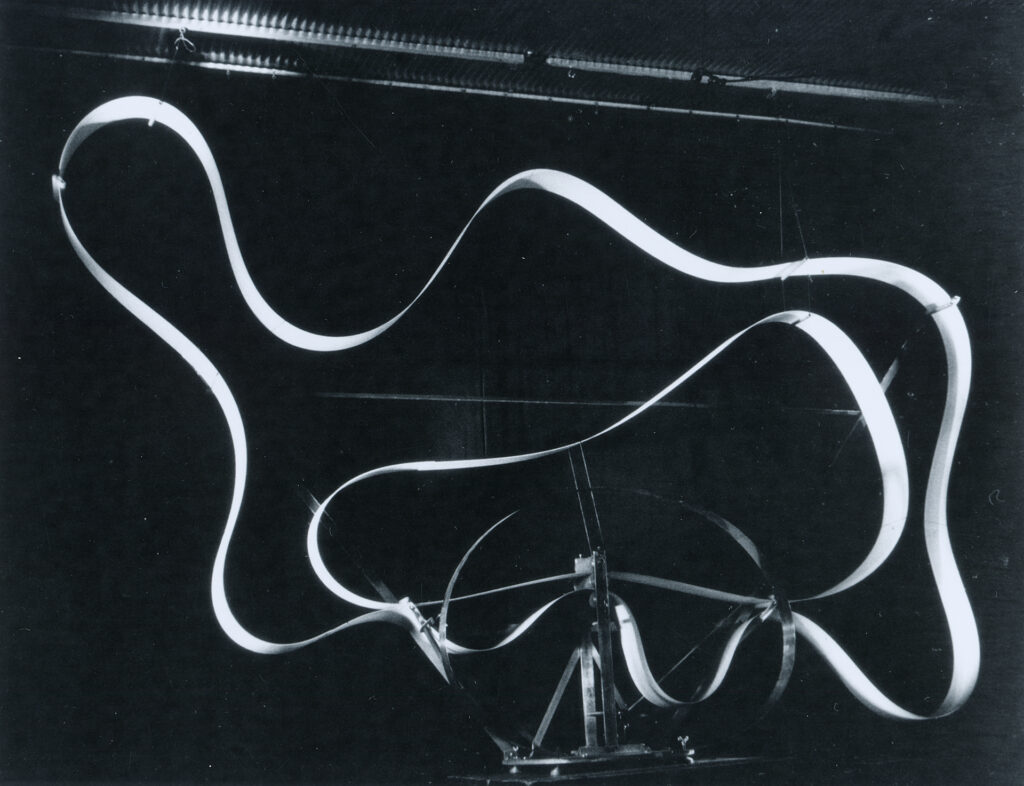

In the late 1950s, Lye began making kinetic sculptures and named them ’Tangible Motion Sculptures’. These sculptures were unlike any other kinetic art being made at the time which focused on geometric forms and hi-tech controls. In contrast, Lye’s work was body orientated, appearing to dance or move realistically, with both energy and vibration.

“So, I went back to animating solid three-dimensional objects, like motion sculpture – something I did as a kid but now I realised that my particular sense of motion was tied in a lot with vibration. And instead of using an old handle to wind pulley-wheels, I used motors to transmit power to the object…a whole lot of springy metals, and the motorized mechanisms would flip them about.”

– Len Lye

Over time, Lye began to see the size of his sculptures as a crucial factor in realistically conveying movement, e.g., a large wave has a vastly different impact and energy from a small wave even though it looks the same. Most of his planned works did not get funded due to the sheer scale, expensive material, and technology they required. Fortunately, the Len Lye Foundation has had the opportunity to produce some of these sculptures over the years from plans that Lye created before his passing.

Prophetically, Lye acknowledged that his “work is going to be pretty good for the 21st century. Why the 21st? It’s simply that there won’t be the means until then, I don’t think there’ll be the means to have what I want, which is enlarged versions of my work.” He entrusted the Foundation with the task of realising his plans for large-scale works once the technology improved and became affordable. Lye’s reputation as one of the most important kinetic sculptors internationally has continued to grow and his work exerts a strong influence on New Zealand’s popular culture.

The Benefits of Digitisation

Digitisation of artwork, like the Len Lye collection, can help art galleries and museums reach a wider audience. Uploading digitised collections online allows anyone to view and engage with the artwork; it can remove geographical limitations and has the potential to destabilise social and economic boundaries which can sometimes plague the art world. Digitisation also aids research about a collection for a broad range of interested parties, for example, access to the entire collection of work in one place enables curators and archivists to make more far-reaching comparisons and produce comprehensive insights about an artist’s practice. It can also help external researchers and students make their own discoveries and offer unique insights about the artworks.

References and Resources

- Gross, M. (2014). Len Lye: Motion Sketch. The Drawing Centre. https://tdc.nyc3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/tdc-1/len-lye-motion-sketch/Press-Release-Len-Lye.pdf

- Len Lye: Motion Sketch. (2014). The Drawing Centre. https://drawingcenter.org/exhibitions/len-lye-motion-sketch

- Len Lye Talks About Art. (n.d.). The Len Lye Foundation. http://www.lenlyefoundation.com/page/len-lye-talks-about-art/4/90/

- Len Lye: The Total Artwork. (n.d.). Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna O Waiwhetū. https://christchurchartgallery.org.nz/exhibitions/len-lye-the-total-artwork

- Ministry for Culture and Heritage. (2017). Len Lye. NZHistory. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/people/len-lye

- Sculptures. (n.d.). The Len Lye Foundation. http://www.lenlyefoundation.com/page/sculptures/70/12/

- Works on Paper. (n.d.). The Len Lye Foundation. http://www.lenlyefoundation.com/page/works-on-paper/70/76/