First-hand accounts of our WW2 veterans are a very precious part of Aotearoa New Zealand’s national history, especially as time passes. Martyn Thompson spent hours interviewing approximately 80 veterans (including 5 women), creating over 79 audio cassettes as part of research for his book “Our War. The Grim Digs. New Zealand Soldiers in North Africa, 1940-1943”, published by Penguin in 2005. The interview process took place between 2001 and 2003 and Martyn had the recordings transcribed. This was a painstaking job that was important for maintaining a true record of what was said, even if some of the audio is indistinct. Now, more than 10 years later, Martyn wanted to ensure these recordings were digitally preserved for future generations to hear the voices of the stories told.

With funding from the Northland District RSA Charitable Trust, and championed by Whangarei RSA member and former Trust Chair, the late Archie Dixon, NZMS has now completed the digitisation of 90 hours of interviews. Martyn has arranged for digital copies to be deposited with Whangarei Museum, Auckland Museum, the National Army Museum and the Alexander Turnbull Library.

He describes how this project began and his experiences meeting the veterans and hearing their stories below:

“In 1998 I found a box in my mother’s cupboard full of letters sent home from North Africa during WW2 by her brother Owen Gatman. Owen was in the 19th and 22nd Battalions and left with the First Echelon of the 2nd NZ Expeditionary force to Egypt in January 1940 and fought in Greece, Crete and Libya in 1941. He was killed in Libya during the Crusader campaign to relieve Tobruk in November 1941.

“Owen was a very skilled letter writer and I thought his words deserved a wider audience and so researched the campaigns and sourced supporting photographs from family members and other soldiers and libraries and put together a book of Owen’s letters titled “On Active Service” which was published in 1999 by Longman.

“A special edition of this book was also used in a fundraising project with the RNZRSA to raise money for veterans in need, The Owen Gatman Memorial Trust was formally launched at a function in Auckland War Memorial Museum by the then Governor General, Sir Michael Hardie-Boys in August 1999 and approx. $50,000 was raised.

Libyan desert scene outside Tobruk.Libyan desert scene outside Tobruk. The campaign fought here in November-December 1941 was the costliest in terms of casualties in a single action for the 2NZEF in the whole of WW2 — 879 were killed, 1699 wounded and 2042 taken prisoner of war.

Libyan desert scene outside Tobruk.Libyan desert scene outside Tobruk. The campaign fought here in November-December 1941 was the costliest in terms of casualties in a single action for the 2NZEF in the whole of WW2 — 879 were killed, 1699 wounded and 2042 taken prisoner of war.

“Each time I was accompanied by a Maori lady; the first one Moira Rolleston, lost her brother Jack Hayward at Belhamed in Libya on the same day Owen was killed in November 1941 and the other, Ngaire Te Paa, lost her brother Wi Te Kowha Hau killed at El Alamein on November 2, 1942 — it was extremely moving to see them reunited with their brothers after 60 years apart.Each time when we travelled across the Egyptian and Libyan deserts the British veterans would talk about their experiences, not just the fighting but the detail of what was involved in living and fighting a war in the Sahara desert – putting up with heat and cold, sand and huge wind storms, flies and dodgy food and limited water.When I returned home after these trips I decided I needed to capture the experiences of our NZ veterans first hand while they were still with us; by 2000 all were at least 80 years old and time was fast running out.

“I contacted the RSA and they gave me names of veterans that were local to me and from both North and South Islands. I tracked down others who had fought with Owen, and others who were not just infantry but who were in different units such as artillery, divisional cavalry, medical, army service corps (transport), ammunition company, signals, YMCA, padres, officers and other ranks, to get a cross section of the 2NZEF as it fought in the North African campaign in 1940 – 1943.

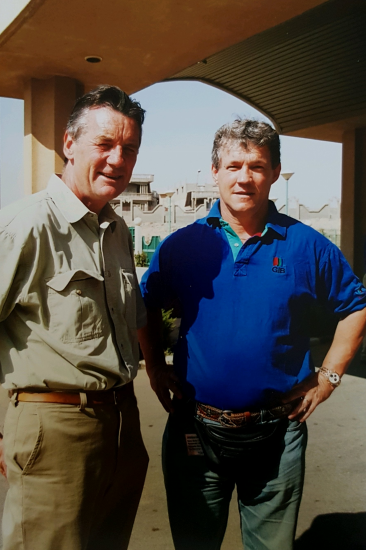

Monty Python star Michael Palin (pictured left) was filming his documentary series ‘Sahara’ in Tobruk, Libya when I was up there in April 2001. He gave my search for Owen’s grave a paragraph in his book that came out to coincide with his TV series.

Monty Python star Michael Palin (pictured left) was filming his documentary series ‘Sahara’ in Tobruk, Libya when I was up there in April 2001. He gave my search for Owen’s grave a paragraph in his book that came out to coincide with his TV series.

“Most of the interviews were done face-to-face although I did a few with soldiers in the South Island over the telephone. I also sourced any photos, drawings and cartoons they might have. Doing these interviews was a wonderful experience… it was like visiting your favourite uncle and aunt… mum would put on the jug and bring out a cuppa and bikkies whilst dad and I chatted in the lounge. Most of these chaps had never talked about their wartime experiences before and I think they thought that this interview was possibly their last chance to talk about what they’d seen and done.”

“Jim Henderson said it best “All really had something to say… Something worthwhile, something deserving recognition, some insistent thread to be part of our national fibre. Something crying at the door of the years”.”

– Martyn Thompson

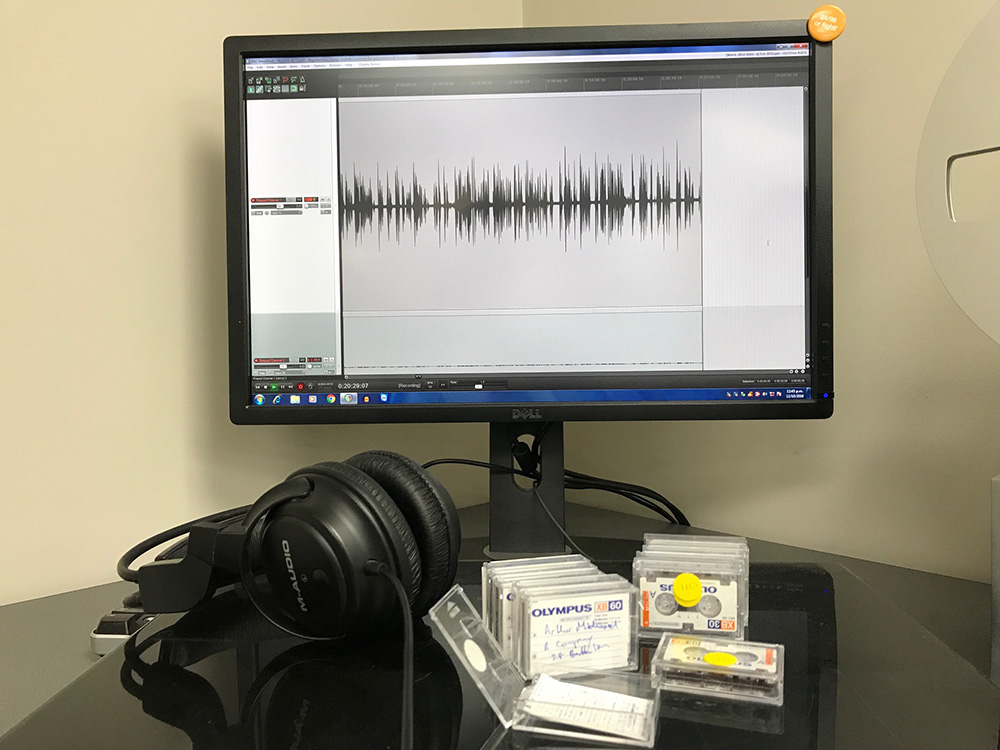

Digitising the Microcassettes

Historically, microcassettes were the main format used in dictation machines and phone answering machines for their ability to store a large amount of content relative to their very small size. About a quarter of the size of a compact cassette, microcassettes were best suited to voice recordings due to their low fidelity; while thinner tape and slower recording speeds allow much longer duration, it reduces the dynamic and frequency range available. Hence, before digital recorders came along, they were ideal for journalists and writers like Martyn Thompson who were recording hours of oral content from interviews.

Like all magnetic tape formats, microcassettes degrade over time and require certain conditions to extend their life and preserve their quality. They prefer a controlled, low temperature, low humidity storage environment out of direct sunlight. Each time a tape is played, tiny iron oxide particles are rubbing off the magnetised surface of the tape and onto the heads and tape guides of the playback machine. Essentially your recorded sound disappears the more a cassette is played over a long period of time, weakening the audio signal stored on it. This pigment rub-off is one of the main reasons why meticulous cleaning is so important prior to digitising.

In order to capture the clearest possible signal and protect the lifespan of our increasingly rare playback machines, all components are cleaned and demagnetised before and after use each day.

To digitise this oral history collection, the microcassette tapes were first physically assessed to determine their condition and whether they required any conservation. They are then played on a microcassette recorder at the speed they were originally recorded at; this ensures the maximum amount of information is captured.

The analogue signal is converted to digital by an AD converter at 24 bits, 96 kHz and recorded on a digital workstation. We use this standard of bit depth and sampling rate to achieve the closest representation of the original recording; simply put, the more samples taken, and the more data allowed in each of those samples, the better the discrete digital signal can mimic the continuous analogue signal.

Once digitised, we undertake quality checks of the recordings to ensure no errors were introduced while “capturing” and whether the audio would benefit from any processing such as noise reduction or phase correction. More about NZMS Audio and Visual Digitisation here.

We encourage anyone with a collection of tapes to bring them in to us for an assessment to ensure that audio or video recordings can be captured and digitally preserved for future generations to enjoy.

From left to right – Martyn Thompson, Jennifer Thompson, Alison Barnett (NZMS), Sheryl Mai (Whangarei Mayor), Frank Lundberg (RSA Bugler), Ian Salter (Whangarei RSA Commemorations Committee), Chris Harold (President, Whangarei RSA), Chas Sibun (Trustee, Northern Districts RSA Charitable Trust), Brian Towgood (Chairman, Northern Districts RSA Charitable Trust

Contact our Audio-Visual Experts today for an assessment of your tapes.