The University of Canterbury (UC)’s Macmillan Brown Library has been working to digitise its extensive collections and have enlisted the help of NZMS. The Macmillan Brown collection was started in 1935, and has since grown exponentially through donations, transfer of existing collections, and selective purchasing by UC. Most notably it holds a diverse range of special collections: the rare books collection, art collection, archives collection, and modern fine print collection.

These cultural heritage collections are an incredibly valuable learning resource; they act as unique primary sources for teaching and help advance research conducted by students, staff, and even wider local and international academic communities.

The rare books collection in particular boasts 7000 volumes of European printed works, including incunabula and medieval manuscripts. One incredibly valuable and unique item from this collection is the Lübeck Bible 1492; there are only 72 known copies of it in existence, and this is the only copy in the southern hemisphere.

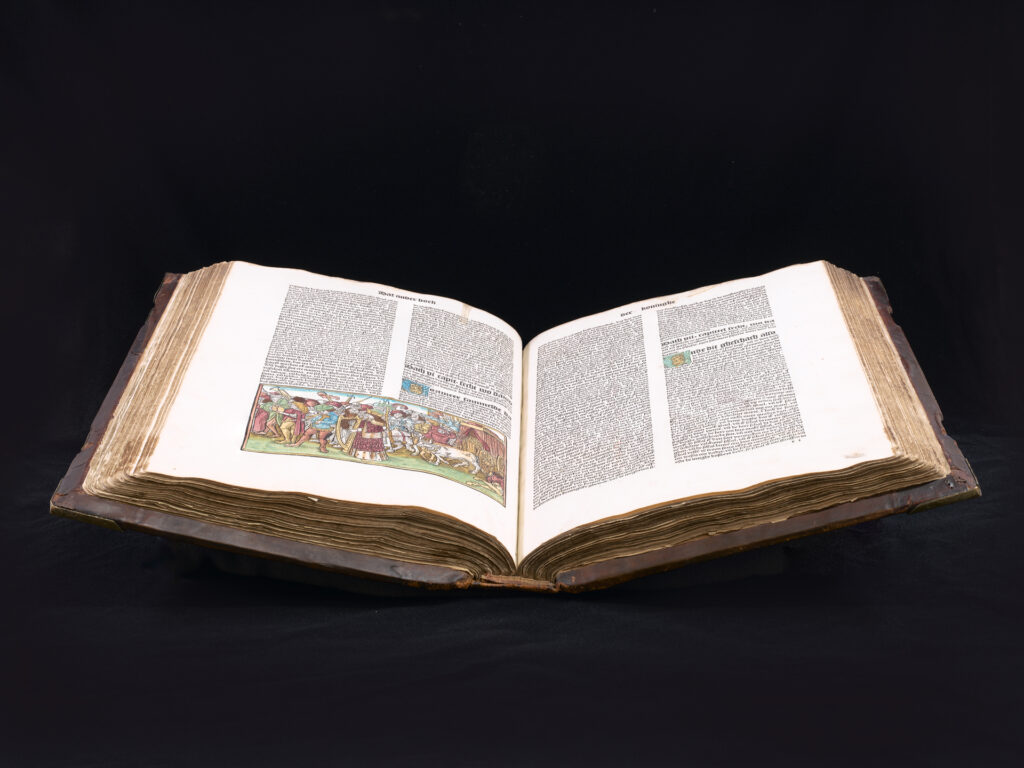

Many surviving copies are incomplete and damaged, while UC’s Lübeck is in comparatively excellent condition. UC’s Special Collections Librarian, Damian Cairns, explains that while it has been described as one of the best remaining copies in the world, this claim remains somewhat of a mystery. Even though it is in very good condition artifactually, it is actually only half of what it should be.

UC’s Lübeck only contains 230 leaves, but a complete copy should contain roughly 490 — it has the entire Old Testament, but none of the New Testament. It is not uncommon for bibles to be separated in this way; for example, Canterbury Museum has half a copy of the 1611 King James Bible. Damian does not know where the other half is, or whether it still exists.

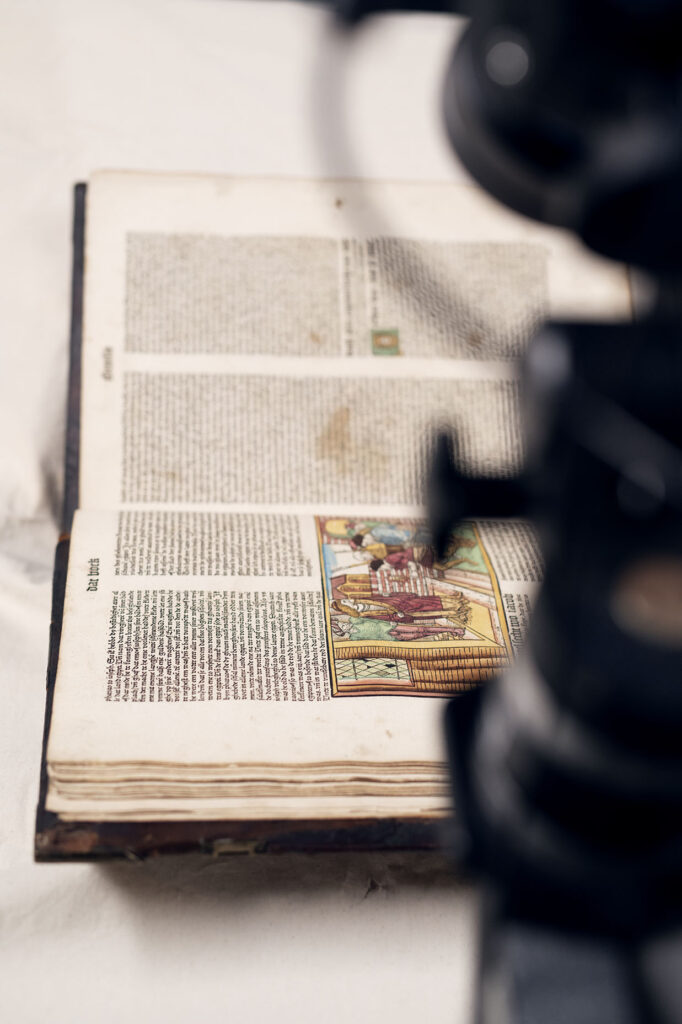

NZMS was given the privilege of digitising this bible, which is beautifully illustrated, and it is one of the oldest items we’ve ever worked with. Our digitisation technicians did not take this responsibility lightly, making sure to handle it with extreme care. We used a Phase One 100 megapixel camera to capture it in intricate detail. The digitisation setup was unusual — it required setting the camera up on a 45-degree angle and capturing the pages one side at a time. This was so the bible did not have to be opened all the way which could have risked damaging the book’s binding.

What makes the Lübeck Bible significant?

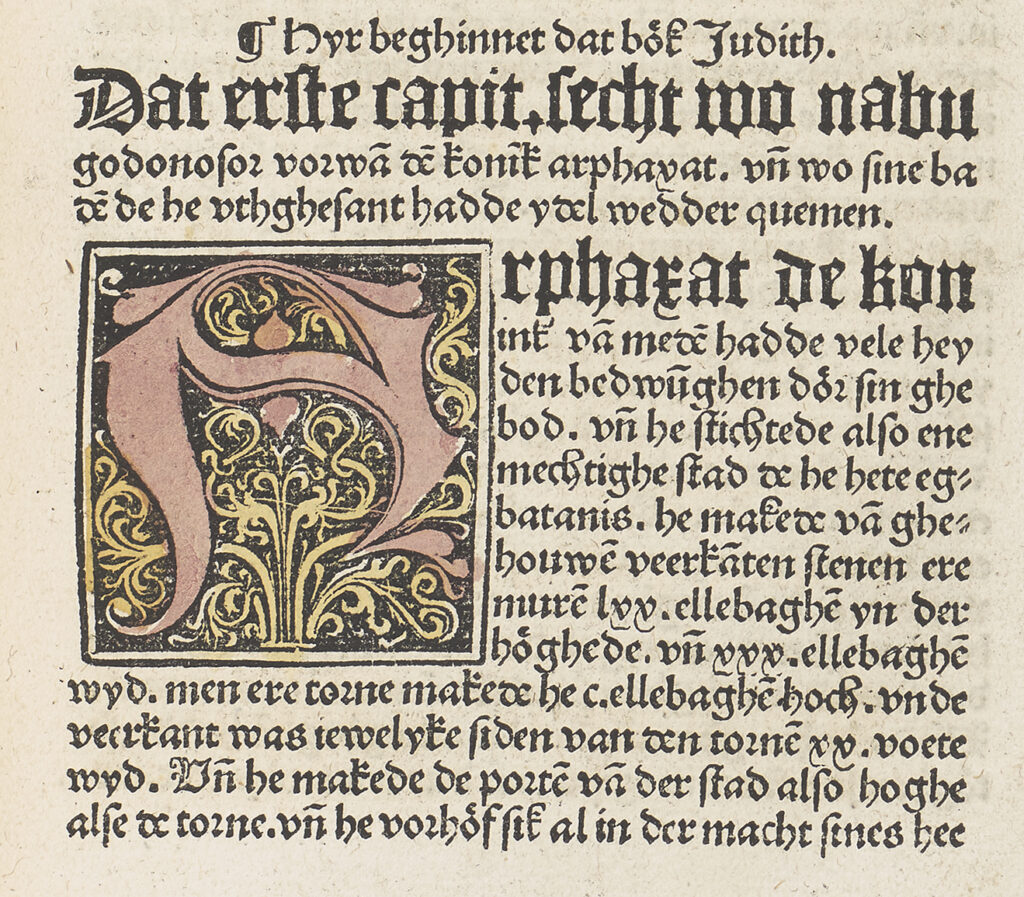

The Lübeck Bible was printed by Steffen Arndes in 1494 and is a Middle Low German edition. Its language, print, and illustration quality make it exceptional compared to other pre-Lutheran German bibles.

The Printer

Steffen Arndes was one of the most influential early printers of the 15th Century and the Lübeck Bible was his masterpiece. The quality of the typography alone makes it stand out, with the beautifully designed and decorated initial letters introducing each paragraph (a jester’s head adorning a capital “U” is particularly well regarded). Arndes also discovered a method to reproduce illustrations in sharp definition, accurately replicating the original artist’s drawing. This is an important innovation because at the time most printed engravings resembled little more than smudges of ink.

The Low German

The Lübeck Bible is a Low German translation which sought to meet the increasing demand for bibles in the vernacular as populations in the urban centres became more literate. However, these bibles were usually translated to a High German dialect which was only spoken by people in Southern and Central Germany. Those who spoke Low German in Northern Germany and the Baltic found these bibles unintelligible.

The Lübeck Bible is only one of four complete bibles in Low German produced before Luther’s testament in 1522; other German bibles were all translated to High German. After the 16th Century, Low German was no longer considered a major literary language and few people spoke it. The Lübeck Bible can therefore be regarded as the last, and possibly greatest, achievements of the Low German dialect.

The Materials

UC’s Lübeck has a contemporary binding: it has a leather cover that has been tooled with an elegant, yet simple design. The furniture (the metal accents on the covers) indicate that it once had clasps. The boards (what is under the cover) are made from heavy European hardwood. Digitisation of the bible was time consuming because the front board, along with some of the first few pages, are detached and needed to be supported carefully to stop any further damage.

The paper is thick and sturdy – it is very high quality for its time period. The Lübeck Bible is made of rag paper, rather than pulp paper, which means it is created from cloth instead of wood. It is quite fibrous and the lines from the production are easily visible. Damian remarked that the paper used for the Lübeck Bible is actually better quality than the paper we use today and will likely outlast contemporary printed material.

The Illustrations

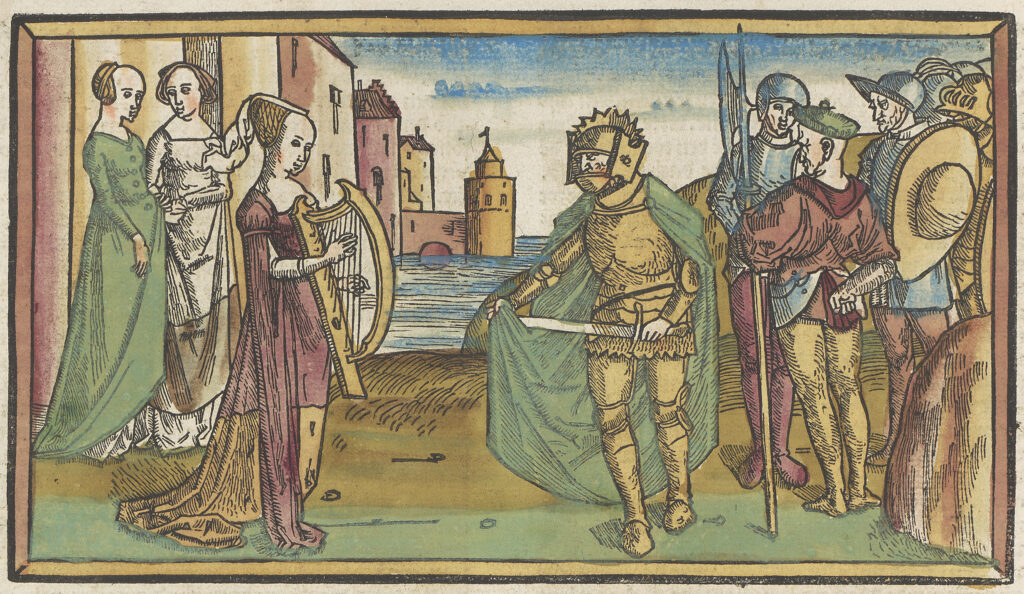

The Lübeck Bible contains 152 woodcut engravings that have been skilfully integrated throughout the book. The illustrations are incredibly unique for their time; they are lively and expressive portrayals of life in the 15th Century.

The UC Lübeck has been enhanced by illuminators unlike any other copy — which points to the owners wealth. Illuminators colour the drawings, similar to colourising black and white photographs. When the illustrations were printed, they would have been simply black and white and whoever purchased it would hire an illuminator to colour the illustrations and add other flourishes.

The exact names of the artists who produced the illustrations are unknown, so they are often referred to as A-Meister and B-Meister.

The A-Meister can be attributed to forty-nine illustrations that are found in the Old Testament. The B-Meister took over creating the remaining illustrations — it is not known why. Scholars generally agree that while the B-Meister was very skilled, the A-Meister was an exceptionally talented artist. The composition of his illustrations are striking and clear, with attention to the intricacies of light and shade, giving the scenes depth and a sense of animation.

William Ivins Jr, curator of the department of prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1916 until 1946), describes how A-Meister imbued his illustrations with life and personality:

“To a degree otherwise unknown in the fifteenth century and for that matter rare enough thereafter, [A-Meister] always saw his pictures in terms of drama. Always there is something doing, always there is striving and conflict of will and emotion and action… He was able to portray anger and disdain and sorrow as no other print maker of his time.”

The Material Culture

The illustrations in the Lübeck Bible allow for a glimpse of everyday life and material culture within Germany during the Middle-Ages. Even though the illustrations tell a biblical story, we are still able to see the architecture of the buildings, the clothes people wore, and even the musical instruments they might have played.

Social Life of the Lübeck Bible

Anthropologist Igor Kopytoff (1986) developed the cultural biography theory which suggest objects accumulate specific biographies, or unique histories, over their lifespan; traces remain identifying an objects different uses, who handled it, and the context in which it existed. This seems true of objects like the Lübeck bible, simply because of its immense age: we imagine who might have owned or read this bible over its 526 years in existence, and as a result we examine it for any clues that might reveal this information.

The Lübeck has lived an interesting life, starting out in Germany and ending up on the other side of the world in New Zealand. The story of how it became part of the Macmillan Brown collection is complex, involving passing through numerous different hands.

Damian, who has been extensively researching the Lübeck bible, explains that the oldest inscription dates to 1588. However, he is still trying to decipher what it says because it has been smudged and crossed out — it can be determined that the bible belonged to the Lutheran Richertz family in the 18th century

The first legible inscription is dated 1700CE and was written by Conrad Rudolph Richertz, the Probus of the monastery church of Butzow which is about 115km from Lübeck. Conrad’s son, Chief Pastor for the Jacob church in Lübeck, George Herman Richertz also inscribed the bible. The Richertz family must have been a family of influence and wealth indicated by the quality of the Lübeck bible’s binding, the leather cover, and the coloured illustrations. A lot of extra money was spent to make it an object of envy.

The next stage in the Lübeck Bible’s journey began when the Richertz family gifted it to the Lübeck Public Library in 1756 — this is known by an inscription in the book but also by the library’s stamp. In 1963, the UC librarian C.W Collins was contacted by the chief librarian of Lübeck City Library who claimed that the bible was stolen from the from them by the Red Army at the end of World War II and that they would like it to be repatriated. Fortunately, Collins was able to prove that it was not the same copy: the stolen one was the full version of the Lübeck Bible while UC’s is only partial, additionally it was already in New Zealand during that period.

After the Lübeck library, it came into the hands of George Theodore Pflüg but how it came into his possession is a mystery. Pflüg was an innkeeper of a hotel in Lübeck called the Hotel Stadt Hamburg — a hotel that is still in operation today. Pflüg then gifted it to the Reverend Arthur Philip Perceval in 1846. Perceval may have been a guest at the Hotel Stadt Hamburg during his ecclesiastical tour of Holland and Germany.

Perceval was a well-known supporter of the Tractarian movement in England and was concerned in the welfare and support of Church of England members living in foreign lands; he provided pamphlets, books, and services to members in Europe. He was a Royal Chaplin for many years but lost this position for performing a service with excessive High Church themes. At the time, there was a split in the Church of England; a disagreement between High Church and Low Church. It is known that during his tour he was denied permission to give a service for members of the Church of England at Lübeck’s Church of St Catherine. Instead he gave his service at Pflüg’s hotel.

Losing the position of Royal Chaplin destroyed his social standing and he lost the respect of his peers. Damian believes that this might have been one of the reasons he gifted works to the Canterbury Association in 1852. This is how the Lübeck ended up in New Zealand — it was included among Perceval’s gifted works. Perceval would have been able to regain some of his social standing and social credibility through this donation because the Canterbury Association had some influential members including Lord Lyttelton.

The gifted works were handed over to Bishop Designate Thomas Jackson whose job it was to amass a library collection for education and ecclesiastical reasons in Canterbury. Bishop Jackson was supposed to be the Bishop of Lyttelton, but that did not eventuate. He came out to Lyttelton for a very short period but returned home before he could become Bishop of Lyttelton — instead Bishop Selwyn was established in the role. Bishop Jackson managed to collect an extensive library, it was first located in the Lyttelton Barracks, where Christs College was originally situated, before moving over the Port Hills into the city centre.

There was a lot of book shuffling between Christs College, Canterbury Museum, and Canterbury College (now called The University of Canterbury). Eventually the Lübeck Bible found its way to Canterbury College in 1939. It was finally catalogued in 1963 by Canterbury College in preparation for the shift to the Ilam Campus. This is where it remains and is currently held at the Macmillan Brown Library in the rare books collection.

Damian believes it is one of the more important and significant items in the rare books collection. He explains,

“There has been limited research on this copy, other than what’s in the Treasures book, and what I’ve done over the last couple of years. It is incunabula, a book printed before 1501, which is a really important period. As far as bound books go, it is the third oldest in our collection. I use it a lot while teaching history and art history because of its artistic merit and as an example of some of the first illustrations produced within printed text in Europe. Its substantial teaching value is why I decided to have it digitised.”

NZMS is honoured to have had the opportunity to play a small role in the Lübeck Bible’s historical journey and we are happy that we could help protect this important piece of cultural heritage.

References and Resources

- Clement, J., Jones, C., & Matthews, B. (2012). Treasures of the University of Canterbury Library (Illustrated ed.). Canterbury University Press.

- Gosden, C., & Marshall, Y. (1999). The cultural biography of objects. World Archaeology, 31(2), 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1999.9980439

- Ivins, W. M. (1932). The Lübeck Bible, 1494. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 27(5), 137. https://doi.org/10.2307/3255352

- Lübecker Bibel (1494). (n.d.). Wikiwand. https://www.wikiwand.com/de/L%C3%BCbecker_Bibel_(1494)

- Steffen Arndes. (n.d.). Wikiwand. https://www.wikiwand.com/de/Steffen_Arndes

- Strand, K. A. (1967). Early Low-German Bibles; the Story of Four Pre-Lutheran Editions. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

- The University of Canterbury. (n.d.). Macmillan Brown Library. https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/library/libraries/macmillan-brown-library/

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. (n.d.). Hanseatic City of Lübeck. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/272/